antibiotic for lung infection

Antibiotic Use in Acute Upper Respiratory Tract Infections - American Family Physician

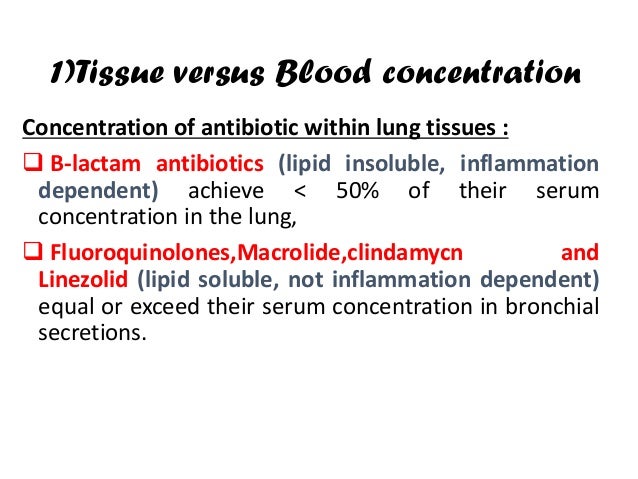

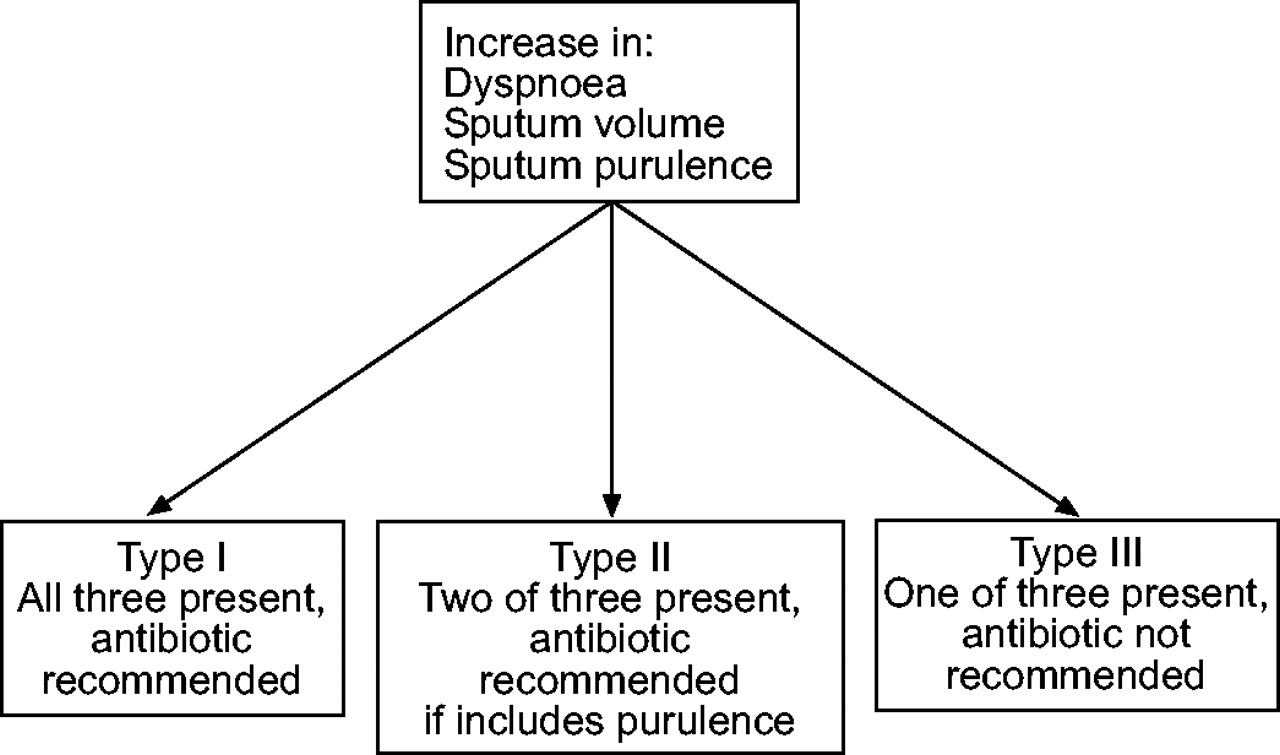

Antibiotic Use in Acute Upper Respiratory Tract Infections - American Family PhysicianMain menu User menuSearchAntibiotic prescription for adults with acute respiratory tos/leal infection: consistent with the guidelines AbstractEuropean guidelines for treating the lower respiratory tract acute tos/infection (LRTI) are intended to reduce the non-substantiation variation in the prescription, and to better aim and increase the use of first-line antibiotics. However, their implementation in primary care is unknown. We explore the consistency of both the antibiotic prescription and the antibiotic election with the guidelines of the European Respiratory Society (ERS)/The European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) for the management of LRTI. The present study was an analysis of prospective observational data of patients who present primary care with acute cough/LRTI. Clinical patients had symptoms in the presentation, and their examination and management. Patients were followed with autocomplete journals.1776 (52.7%) patients were prescribed antibiotics. Given the clinical presentation of patients, doctors may have justified an antibiotic prescription for 1,915 (71.2%) patients according to ERS/ESCMID guidelines. 761 (42.8%) of the prescribed antibiotics received a first-choice antibiotic (i.e. tetracycline or amoxicillin). Cyprofloxacin was prescribed for 37 (2.1%) and cephalosporins for 117 (6.6%). The lack of specificity in the definitions of ERS/ESCMID guidelines could have allowed doctors to justify a higher rate of antibiotic prescription. More studies are needed to produce specific clinical definitions and indications for treatment. First-choice antibiotics were prescribed to the minority of patients who received an antibiotic prescription. European guidelines have been developed and promoted to reduce the variation of unsupported and unsupported care. Guidelines for the management of suspicious infections should help clinicians to better target antibiotics by prescribing the most likely to benefit and increasing the proportion of recipes for frontline agents in the hope that this will result in more effective care, a reduced risk to patients and help contain resistance to antibiotics. In collaboration with the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) published guidelines on when and what antibiotics should be prescribed in patients with lower respiratory tract (LRTI) infection in primary care []. The promoters of the guideline face difficulties arising from gaps in the basis of supporting evidence and, therefore, some recommendations are based on consensus and commitment rather than empirical evidence. It is not known to what extent the practice of real prescription throughout Europe is consistent with such key guidelines in primary care. The future observational GRACE (Genomics to Combat Resistance Against Antibiotics in Community-Acquired LRTI in Europe; ) 01 study of the presentation, management and outcome of acute cough in primary care identified a considerable variation in the prescription of antibiotics for acute cough in Europe that could not be explained by variation in clinical presentation, and that it was not associated with clinically important differences in recovery [, ]. An important reason why this study focused on adults is because the largest number of antibiotic prescriptions for LRTI is for this age group []. Here, we explore the extent to which the level of antibiotic prescription and actual antibiotic choice to treat acute cough was consistent with the recommendations in the ERS/ESCMID guidelines. MATERIALS AND METHODS Eligible patients were: older than ≥18 years; they were consulted with a disease where a cough or worsened was the main or dominant symptom, or had a clinical presentation that suggested an LRTI, with a duration of ≤28 days; first-time consultation within this episode of disease; seen within normal hours of consultation; had not previously participated in the study; they were able to fill in study materials; they had provided informed consent in writing; Participants were asked to hire patients with consecutive right from October to November 2006 and the end of January to March 2007. Study Design Germany, Spain, Hungary, Poland, United Kingdom, Finland, Sweden, Sweden, Sweden, Sweden, Spain, Mexico, Spain, Finland, Poland, United Kingdom, Finland, Poland, United Kingdom, United Kingdom, United Kingdom, United Kingdom, United Kingdom, United Kingdom, United Kingdom, United Kingdom, United Kingdom, United Kingdom, United Kingdom, United Kingdom, Spain, Mataro, Spain; Lotenberg pulmonary, Germany; Balatonfured, Hungary Clinical aspects (GP and nurse) If an antibiotic was prescribed, the doctor was asked to register the name of the antibiotic. The antibiotics were later categorized into classes, informed by subcategories of the British National Formula []. Clinical patients recorded the presence or absence of cough (among others), lack of breath, production of flems and color, and fever during the disease, and then valued the severity of the symptoms at a scale of four categories. Patients received a symptom diary. They were asked to evaluate 13 symptoms every day until recovery (or for 28 days if the symptoms were ongoing) on a seven-point scale from "normal/unaffected" to "as bad as it may be." The diary also asked how many days were not well before seeing your GP or nurse for their cough. Variables ERS/ESCMID guidelines list six subgroups of patients in which antibiotics should be considered: those with suspicious or defined pneumonia; those with selected exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); those of 75 years with fever; those with heart failure; those with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; and those with severe neurological disorder. Proxied these subgroups using CRFs and diary data (supplementary material ). PneumoniaThe ERS/ESCMID guidelines define suspicious or defined pneumonia as acute cough and one of: 1) new focal signals; 2) dyspnea; 3) tachypnea; and 4) 4-day fever. This was stimulated by having an acute cough and one of: 1) decrease of vesicular breathing, cracks or rhonchi; 2) shortness of breath; 3) tachypnoea was modeled by the respiratory rate ю20 breaths·min−1 [, ]; and 4) fever (temperature √37.8 °C) in patients who had waited ≥4 days before consulting their GP or nurse. COPDThe guidelines indicate that the selected exacerbations of COPD when antibiotics are indicated require a diagnosis of COPD and the three of: 1) increase in dyspnea; 2) increase in sputum volume; and 3) greater purity of sputum or diagnosis of severe COPD (i.e., patients with severe exacerbation that requires invasive or non-invasive mechanical ventilation). Let's go this by selecting those patients in our COPD study and all: 1) shortness of breath; 2) flem production; 3) yellow, green or blood-stained flem color, or with an oxygen saturation measured by pulse oxide (Sp,O2) Fever in the elderlyFCI data on the age and fever of patients (defined as body temperature Ø37.8°C) are recorded Heart failure The heart failure was considered to be present if a doctor had a diagnosis of heart failure. Insulin-dependent diabetesMellitus insulin-dependent diabetes was considered to be present if a doctor registered a diagnosis of diabetes and the patient was taking insulin regularly. Serious neurological disorders No information was collected on serious neurological disorders. Antibiotics Guidelines recommend tetracycline and amoxicillin as "preferred" antibiotics. In cases of hypersensitivity, macrolides are recommended as an "alternative" antibiotic. When there are clinically relevant bacterial resistance rates against all first-choice agents, levofloxacin and moxifloxacin are also recommended as an "alternative." Amoxicillin–clavulanate is also included as an appropriate "alternative" antibiotic. First, we evaluate the consistency of the ERS/ESCMID guide with respect to the decision to prescribe or not antibiotics for acute coughing/LRTI (antibiotic prescription analysis). We distinguish between "congruent prescribing", "congruent not to prescribe", "not congruent to prescribe" and "not congruent not to prescribe." Secondly, we evaluate the proportion of the consistency of the guideline with respect to the choice of antibiotics in those patients who were prescribed an antibiotic (antibiotic election analysis). Statistical methodsDescriptive statistics are presented for the prescription of antibiotics and antibiotic type compared to the guidelines. These are also presented by the network to explore the variation of congruence throughout Europe. RESULTSParticipants387 practitioners recruited 3,402 patients. Six networks included ≥270 patients and all included √100. Four patients were later found ineligible and were therefore excluded from a deeper analysis. FCI was completed for 3,368 (99%), which were included in the analysis of antibiotic options. Daily data were obtained from 2,714 patients (80%). 2.690 (79%) completed both the FCI and the journal, and were included in the antibiotic prescription analysis. Patients not included in this last analysis were younger and less frequently antibiotics, but were similar to patients included in terms of sex, clinical presentation and comorbidities. Descriptive data Participants were at a mean age of 48 (interquartile range (IQR) 35–60 years). 36.2% were men, 5.8% had COPD, 1.7% had heart failure and 4.7% had diabetes. Regarding the symptoms used for proxy ERS/ESCMID guidelines, 99.8% had cough, 50.7% had lack of breath, 77.1% had flem production and 46.5% had purulent sputum. Patients were not well for a median of 5 days (IQR 3-8 days) before consulting their GP. The average temperature was 36.8°C (IQR 36.4–37.2°C). Main results Antibiotic prescriptions An antibiotic was prescribed to 1,776 (52.7 per cent) of 3,368 patients with completed IF. We could only include 2,690 patients in the rest of the antibiotic prescription analysis, as both full daily questionnaires and patients were required to obtain all proxy data. Of these 2,690 patients, little more than half (n = 1,464; 54.4%) were prescribed an antibiotic (). Our exploratory analysis suggests that clinicians may have justified an antibiotic prescription by 71.2% (n = 1.915) by a literal reading of ERS/ESCMID guidelines. In 1,745 (64.9%) patients, the decision to prescribe was consistent with the ERS/ESCMID directive (). shows the distribution of antibiotic types observed in each network. It was observed 45.2 per cent congruent prescribing, 19.6 per cent congruent without prescribing, 9.2 per cent non congruent prescribing and 25.9 per cent non congruent (). it provides information on the percentages of each type of prescribing prescribed by network, and this is graphed in . Chart of scalonate bars of the percentages of antibiotics grouped according to the recommendations of the European Respiratory Society. Graph of stacked bars of the percentages of antibiotics that prescribe the consistency of the decision to the European Respiratory Society/European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases recommendations of network guide. It is estimated that 70.8% of patients may have been considered as suspicious or defined pneumonia according to our exploratory analysis; other reasons were less common (2.9% of the selected COPD exacerbations; 0.4% of the 75 years with fever; 1.7% heart failure; 0.9% insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; no data for severe neurological disorder). However, clinicians reported pneumonia as their diagnosis of work in only 4.3% of cases (other working diagnoses included LRTI (44.8%), upper respiratory tract infection (25.9%), general viral infection (10.5%), non-specific respiratory infection (3.4%), cough (3.3%), asthma (3.2%), COPD (3%), other non-specific (0.6%) and hyperresponsibility (0.4%). To investigate this later, a sensibility analysis was performed to make the definition of suspicious or definitive pneumonia modified from acute cough and one of 1) new focal signs of chest, 2) dyspnea, 3) tachypnea and 4) 4-day fever, to acute cough and two of the symptoms mentioned above. Under these new conditions, the percentage of suspicious or definitive pneumonia was reduced to 27.8 per cent and the overall percentage in which an antibiotic could be justified was reduced from 71.2 per cent to 29.7 per cent. Increase the number of symptoms required to three reduced the percentage with suspicious or defined pneumonia to 3.1 per cent and the percentage to be considered for the antibiotic prescription to 8.0%. An additional sensitivity analysis was performed on the breast signs, as no details were recorded on new focal signs, as defined in the guidelines. Excluding breast signs completely reduced the proportion of patients for whom an antibiotic could have been justified from 71.2% to 53.6%. Antibiotic Choice Of those prescribed an antibiotic, first-choice antibiotics tetracycline or amoxicillin were prescribed for 761 (42.8%), 773 (43.5%) received a prescription for an alternative antibiotic and 242 (13.6%) received an antibiotic not recommended by the ERS/ESCMID guidelines (including 37 (2.1%) receiving ciprofloxacins and 117 (6.6%) receiving cephalos. Most patients in eight of the 14 networks received a first-choice antibiotic. In Utrecht, 89.2% of the prescripts received a top-ranking agent, compared to Milan, where only 9.7% are prescribed amoxicillin or tetracycline. In 518 (42.6%) of 1,217 patients who were prescribed an antibiotic compatible with ERS/ESCMID guidelines, the antibiotic option was also consistent with ERS/ESCMID guidelines (). In other patients, they prescribed an antibiotic (non-congruent prescription), this proportion was 76 (30.8%) of 247 patients. DISCUSSION Major results In general, an antibiotic was prescribed in 1,776 (52.7%) patients with acute cough/LRTI in this study of 13 countries, prospective and observational primary care. It is estimated that doctors, if so much attention had been paid to them, could have justified the prescription of antibiotics for an even greater number of patients (70 per cent concentration) through a literal interpretation of ERS/ESCMID guidelines on the management of acute LRTI. Tromsø was the less congruent recipe network, with 55.4% antibiotic prescription decisions not consistent with the ERS/ESCMID guide. This is largely explained by patients who are not prescribed an antibiotic when the guidelines could have justified an antibiotic prescription. However, this network prescribed antibiotics to a low proportion of patients and generally used narrow agents. This highlights the precaution to be applied to interpret this aspect of the analysis. A first-choice antibiotic (according to ERS/ESCMID guidelines) was prescribed to 761 (42.8%) patients; 773 (43.5%) received a recommended alternative antibiotic and 242 (13.6%) were prescribed an antibiotic that was not recommended by the guidelines. However, agents such as ciprofloxacin (2.1%) and cephalosporins (6.6%) were not widely used. Strength and Limitations The wide range of inclusion criteria allowed patients with community-premied LRTI to be analyzed, presenting a number of symptoms. We use the data we collect to the proxy criteria specified in the guidelines. This increased the probability of error in our prescription analysis. For example, we did not collect data on new focal signs of the chest, so the auscultation findings were used on the day of consultation. We don't know how many of these auscultation anomalies were, in fact, new signs. However, in practice, many patients are seen by doctors who would not know if the abnormalities in the auscultation were new or not. We do not ask the clinicians to distinguish between focalized and widespread abnormalities in the auscultation. This could have led to an overestimation of those for whom a prescription had been justified, as ERS/ESCMID guidelines consider antibiotics to be indicated in the case of focal anomalies. Sensitivity analysis showed that the exclusion of patients with breast signs would still mean that an antibiotic could have been justified (based on other findings) in most patients. We couldn't identify patients with severe neurological disorder. In addition, some measures ( respiratory rate and Sp,O2) used to evaluate the symptoms were not performed in all patients of the study, as these tests were performed at the discretion of doctors. Patients with diabetes mellitus taking insulin were considered equivalent to patients with insulin-dependent diabetes, but this might have included people with type II diabetes who were treated with insulin. The duration of the fever was not recorded during the presentation, so we had to make the assumption that the duration of the disease ≤4 days before the implicit consultation fever 4 days, if the fever was present at the consultation. We are aware that different countries may have followed their own national guidelines and, in some cases, a guideline from all over Europe may not be appropriate. The selection bias of doctors and patients may have affected the results. Since research networks are likely to include the most "orientation-conscious" professionals, the true rate of adherence to the guidelines in primary care in Europe may be lower than that described in this study. We asked doctors to recruit sequential patients in the study, but since they were unable to keep records of eligible patients, we do not know what proportion of eligible patients was recruited. More patients may be recruited at less busy times. Patients who were willing to the doctors may have been overrepresented. Interpretation The achievement of guidelines in daily clinical care remains a challenge, with a recent study that some clinicians consider that resistance to antibiotics is not affected by their practice and that some doctors prescribe broad-spectrum antibiotics for some IRTL patients in order to give their patients the best chance to recover and prevent hospital income []. Additional research should generate a better understanding of the capture of sub-optimal guides and identify opportunities for the development of intervention. Guidelines may also allow doctors to justify antibiotic prescriptions in more cases than anticipated, especially when definitions are widely specified because of a suboptimal test basis. Guideline developers face many challenges, including making treatment recommendations in the context of imperfect testing. It should be recognized that, while the guidelines suggested that clinicians consider antibiotic treatment when certain signs or symptoms occurred, they do not say that antibiotic treatment is justified in all patients with these symptoms. In addition, the very broad definition of suspicious pneumonia emerged from the lack of evidence of rigorous diagnostic studies in this field [, , ].Implications for practice and researchThe previous research has identified both about- and sub-prescribe antibiotics for common infections in primary care [, ]. Overprescribing risks unnecessarily by exposing patients to the risk of side effects without achieving significantly faster recovery []. This also affects the transport of antibiotic-resistant organisms [], the risk of infection with resistant organisms [], the recovery and workload of patients in general practice [], and the costs [].However, the reduction of prescription at general practice level has been associated with reductions in antibiotic resistance locally []. Subprescribing may result in increased risk of pneumonia identified in retrospective studies using general practice in the form of data routinely collected [, ].Our study has identified an opportunity to minimize the non-substantiation of evidence in the prescription of antibiotics throughout Europe, despite the existence of a relevant European directive []. Achieving an understanding of the reasons for adherence to the sub-optimal guideline is an urgent requirement to intervene in development aimed at improving practice. Antibiotic choice often varies from the recommendations of the guideline and, in its current form, ERS/ESCMID guidelines could be used to justify the increase in antibiotic prescription if applied literally. The narrower definitions of suspicious pneumonia can improve future versions of this guideline. More diagnostic research is needed in primary care to allow this. Acknowledgements We recognize the entire GRACE team for its diligence, experience and enthusiasm. The GRACE team are: Z. Arvai (DRC Ltd, Balatonfured, Hungary), Z. Bielicka (Clind Research Associates and Consultants, Bratislava, Slovakia), A. Borras (CAPSE, Barcelona, Spain), C. Brugman (University Medical Center Utrecht, Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, Utrecht, Birmingham) We would also like to recognize the help of V. McNulty (Cardiff University) in the completion of this manuscript. NotesFor editorial comments see . This article has supplementary material available in the Declaration of Support This study was funded by the Sixth Framework Programme of the European Commission (LSHM-CT-2005-518226). The South Wales Trial Unit is funded by the Wales Research and Development Office. The financiers had no role in the design and realization of the study, nor in the collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data, nor in the preparation, approval of the reviewer of this manuscript. C. Butler had full access to all the data in the study and was responsible for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Statement of Interest Statements of interest to T. Verheij, A. Torres and T. Schaberg can be found in REFERENCESThank you for your interest in spreading the word about the European Respiratory Society. NOTE: We only request your email address so that the person you are recommending the page knows that you wanted to see it, and that it is not junk mail. We don't capture any email address. FormatsJump ToSubject ISSN More in this section of the TOCOriginal articleRelated respiratory infections ArticlesNavigate About ERJEuropean publications of the Respiratory Society HelpFor Authors For readers SubscriptionsContact usThe European Respiratory Society442 Glossop RoadSheffield S10 2PXUnited KingdomTel: +44 114 2672860Email: journals@ersnet.orgISSNPrint ISSN online: 1399-3003 Copyright © 2021 by the European Society of Respiration

Antibiotic stewardship intervention improves prescribing for acute respiratory infection | EurekAlert! Science News

Choice of antibiotic in respiratory infections

Reducing Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing for Acute Respiratory Tract Infections

Effectiveness of clinical pathway for upper respiratory tract infections in emergency department - International Journal of Infectious Diseases

Reducing Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing for Acute Respiratory Tract Infections

Effectiveness of clinical pathway for upper respiratory tract infections in emergency department - International Journal of Infectious Diseases

Drug improves antibiotic treatment of lung infection

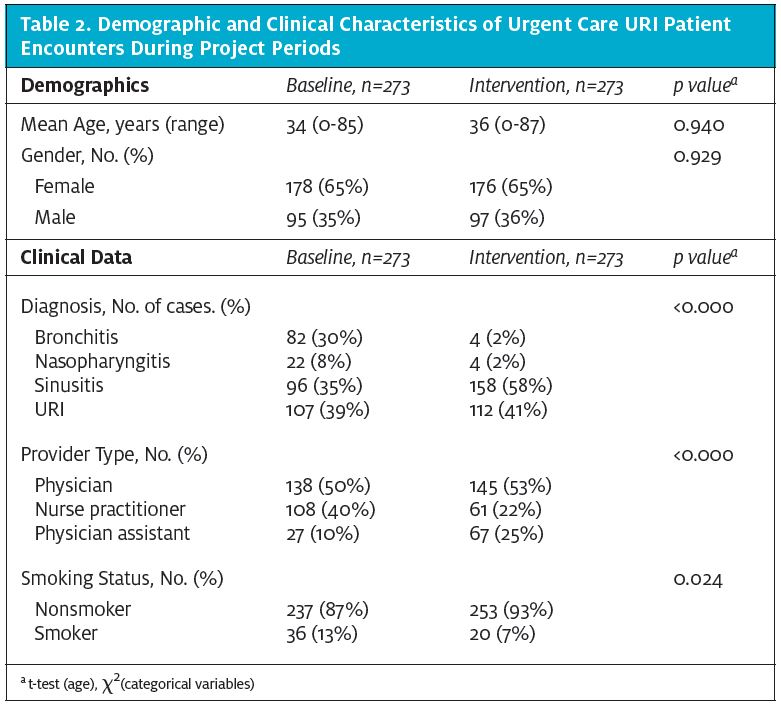

A Multimodal Intervention to Reduce Antibiotic Use for Common Upper Respiratory Infections in the Urgent Care Setting | Journal of Urgent Care Medicine

Use of antibiotics in upper respiratory infections on patients under 16 years old in private ambulatory medicine

Reducing Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing for Acute Respiratory Tract Infections

Improving antibiotic prescribing in acute respiratory tract infections: cluster randomised trial from Norwegian general practice (prescription peer academic detailing (Rx-PAD) study) | The BMJ

Chest Cold (Acute Bronchitis) | Community | Antibiotic Use | CDC

Treatment of community-acquired lower respiratory tract infections in adults | European Respiratory Society

Acute Respiratory tract infections for the use of antibiotics. | Download Table

Empiric antibiotic therapy for the treatment of nontuberculous... | Download Table

Antibiotic Use in Acute Upper Respiratory Tract Infections - American Family Physician

Antibiotic Strategy in Lower Respiratory Tract Infections

Effect of procalcitonin-guided treatment on antibiotic use and outcome in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster-randomised, single-blinded intervention trial - The Lancet

Steroids not effective for chest infections in adults who don't have asthma or other chronic lung disease — SPCR

Guidelines for the management of adult lower respiratory tract infections | European Respiratory Society

Antibiotic Use in Acute Upper Respiratory Tract Infections - American Family Physician

Antibiotics Needed for Lower Respiratory Tract Infections? | RT

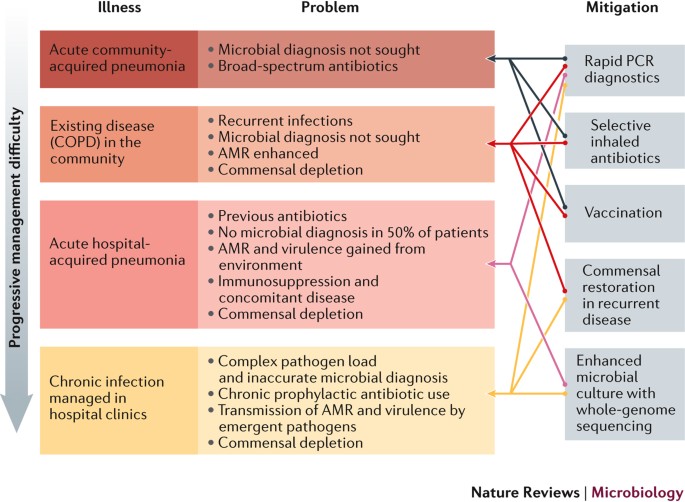

New opportunities for managing acute and chronic lung infections | Nature Reviews Microbiology

Using antibiotics wisely for respiratory tract infection in the era of covid-19 | The BMJ

ANTIBIOTIC VISITS PRESCRIPTION RATE FOR UPPER RESPIRATORY TRACT... | Download Table

Systemic antibiotic treatment in upper and lower respiratory tract infections: official French guidelines - - 2003 - Clinical Microbiology and Infection - Wiley Online Library

Respiratory tract infection - Wikipedia

Effects of internet-based training on antibiotic prescribing rates for acute respiratory-tract infections: a multinational, cluster, randomised, factorial, controlled trial - The Lancet

Chest Cold (Acute Bronchitis) | Community | Antibiotic Use | CDC

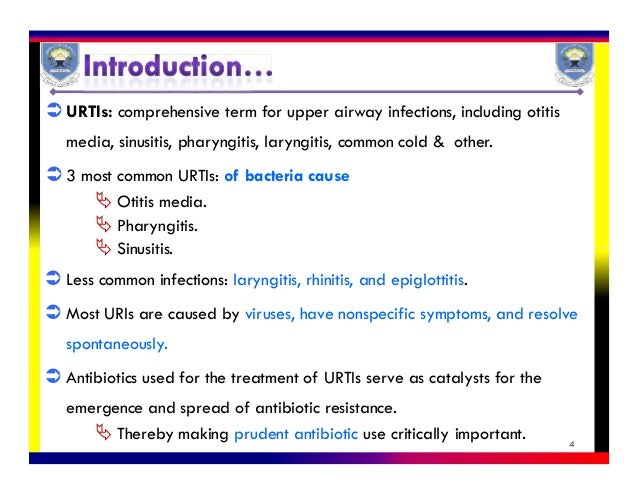

Upper respiratory tract infections

![PDF] Guidelines for the Antibiotic Use in Adults with Acute Upper Respiratory Tract Infections | Semantic Scholar PDF] Guidelines for the Antibiotic Use in Adults with Acute Upper Respiratory Tract Infections | Semantic Scholar](https://d3i71xaburhd42.cloudfront.net/9572c5aae9bef12492279374fa1f562a03eafd08/19-Table8-1.png)

PDF] Guidelines for the Antibiotic Use in Adults with Acute Upper Respiratory Tract Infections | Semantic Scholar

RACGP - Addressing antibiotic resistance – focusing on acute respiratory infections in primary care

A framework for the non‐antibiotic management of upper respiratory tract infections: towards a global change in antibiotic resistance - Essack - 2013 - International Journal of Clinical Practice - Wiley Online Library

Cystic Fibrosis Lung Infections: Polymicrobial, Complex, and Hard to Treat

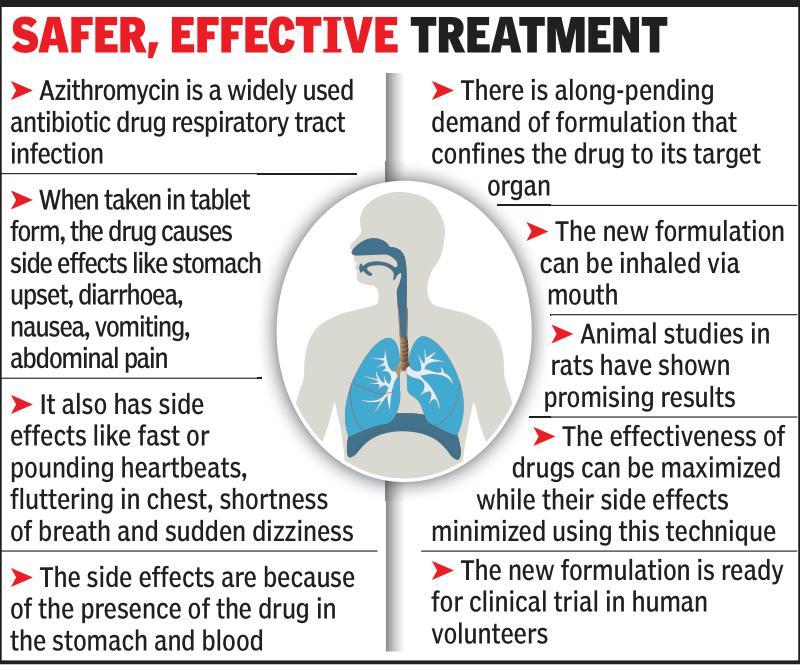

No more popping pills, now just inhale your antibiotics! | Vadodara News - Times of India

How Well Antibiotics Work for Cystic Fibrosis Patients May be Affected by pH, Oxygen | Research at Michigan State University

Azithromycin 250mg One A Day Side Eff... - British Lung Foun...

Long-term macrolide treatment for chronic respiratory disease | European Respiratory Society

PLOS ONE: A Biomathematical Model of Pneumococcal Lung Infection and Antibiotic Treatment in Mice

Pneumonia: Antibiotics Not Effective

Posting Komentar untuk "antibiotic for lung infection"